Will high wages and high skills mean high house prices?

The puzzling property problem

In his conference speech this week, Boris Johnson said that we are moving towards a high wage high skill economy, but will this also mean high house prices? And if it does, how will higher house prices impact the Government’s desire to solve the national productivity puzzle by fixing the broken housing market?

House prices and wages

The majority of home purchases in the UK are part-financed with a mortgage. Mortgage capacity is directly linked to the borrower’s earnings. In our view, borrowers tend to borrow towards the top end of their mortgage capacity. Higher wages will, therefore, feed into higher mortgage capacity, which, in turn, will put upward pressure on house prices.

House prices and mortgage rates

The mortgage rate effectively determines the ‘cost’ of the mortgage. The higher the mortgage rate the lower a borrower’s mortgage capacity. Today, mortgage rates are close to all-time lows, so over the longer term, they are more likely to move up than down. Rising mortgage rates would put downward pressure on house prices for those reliant on mortgage finance to buy their home.

The broken housing market

In the 2017 White Paper ‘Fixing our broken housing market’, the UK Government said:

“Our broken housing market is one of the greatest barriers to progress in Britain today. Whether buying or renting, the fact is that housing is increasingly unaffordable.”

At the time the Prime Minister, Theresa May said:

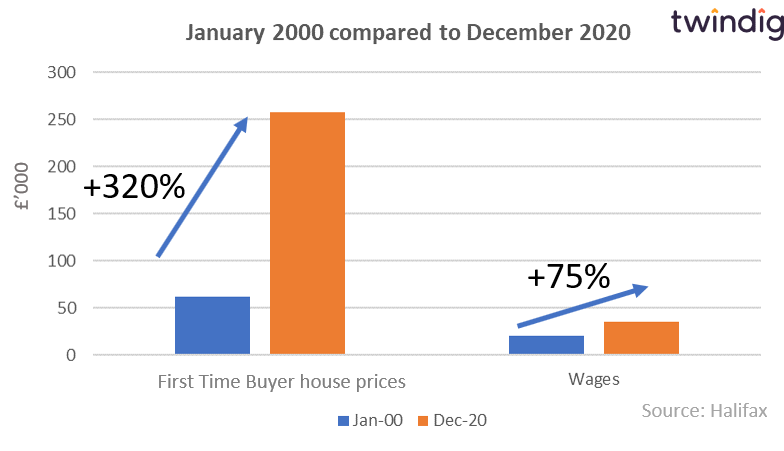

“Today the average house costs almost eight times average earnings – an all-time record. As a result, it is difficult to get on the housing ladder, and the proportion of people living in the private rented sector has doubled since 2000.”

“I want to fix this broken market so that housing is more affordable and people have the security they need to plan for the future.”

It seems that the Conservative’s believe that affordability is the main cause of the broken housing market, and yet because of the multiplier effect of mortgages (you can borrow a ‘multiple’ of your earnings) as wages rise the amount you can borrow to buy a home rises at a faster rate than wages, which compounds rather than tempers the housing affordability problem.

Build houses and house prices will fall?

The Government believes that we can build our way out of the housing crisis, that we can fix the broken housing market by building more homes. This may work in the GCSE level Economics textbook, but in the real world, life is not as simple. For an interesting set of thought experiments on why building more homes won’t necessarily lower house prices, I recommend reading Alastair Parvin’s blog If the UK built 1 million homes, what would happen to house prices?

It is difficult to build enough homes in the right places and as Alastair points out, building more homes may raise prices in an area if it lifts the ‘buzz’ of living there and increases the level of services and amenities.

95% mortgages are debts, not silver bullets

This week, when addressing the broken housing market, Prime Minister Boris Johnston said

“We have not only built more homes than at any time in the last 30 years, we are helping young people on to the property ladder with our 95 per cent mortgages”

As we have already mentioned, building more homes is not necessarily the answer and we do not believe that 95% mortgages are a silver bullet either. An arrow in a quiver? Yes, but not the whole shooting match.

Whilst a 95% loan to value mortgage helps with the problem of raising a deposit, it is of no help in bridging the gap between wages and house prices. You may be able to borrow 95% of the value of the home, but if the value of that home is more than 4.5x your earnings you are unlikely to be able to secure a large enough 95% mortgage to purchase the home. The problem is then put back into the lack of deposit court.

Fixing the housing deposit problem

As long as homebuyers can borrow multiples of their income to buy a home, in the absence of changes in mortgage rates, house prices are likely to rise faster than wages exacerbating the affordability problem.

We believe that the main barrier to homeownership is securing a large enough deposit. If you solve the deposit problem, we believe you will fix the broken housing market.

We continue to believe that fractional ownership is the key to fixing the broken housing market. Allow others to co-invest alongside aspiring homebuyers, an extended family version of the bank of mum and dad. There is no easy way for UK adults to invest in residential property apart from actually buying a home.

Imagine if it was possible to invest in UK residential property via an ISA or a pension fund. Those wanting more exposure to the UK housing market would be helping first-time buyers to buy.

As a nation, we like investing in property, but we find pensions dull and uninteresting. Most adults in the UK do not save enough for their pension despite attractive tax breaks and employer contributions. However, those same adults do not need nudging, encouraging or reminding to invest in property. If we could enable property investing to become pension savings we may have found a win-win solving the housing crisis and the pension crisis at the same time.