Right to buy extension: Right or wrong?

Today (9 June 2022) the Prime Minister announced that 2.5 million tenants renting their homes from housing associations will be given the right to buy them outright

This ‘new’ policy is an extension of the original Right to Buy scheme launched 42 years ago by the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

In this article, we look at whether the Right to Buy is right or wrong

What is Right to Buy?

The original Right to Buy was enshrined in the 1980 Housing Act. At the time around one-third of the population lived in council-owned properties and now anyone who had lived in their council house for more than three years was entitled to own it.

To sweeten the purchase council house tenants were given a discount to the market value, starting at 33% for tenants with three years of tenure, rising to 50% for those with a tenure of 20 years or more, the discounts were capped at a maximum of £50,000. This discount was very generous when we consider the average property price in 1980 was less than £25,000.

Right to Buy purchasers were also guaranteed 100% mortgages by the local authority.

Did Right to Buy work? (Take 1)

Yes. By the end of 1982, more than 240,000 council tenants have purchased their homes through the Right to Buy scheme

In the 42 years since the Right to Buy scheme was launched, almost 2 million social housing tenants have purchased their homes through Right to Buy.

Did Right to Buy work? (Take 2)

No. According to the housing charity Shelter, fewer than 5% of the homes sold through Right to Buy have been replaced, the stock of council housing has therefore dropped dramatically.

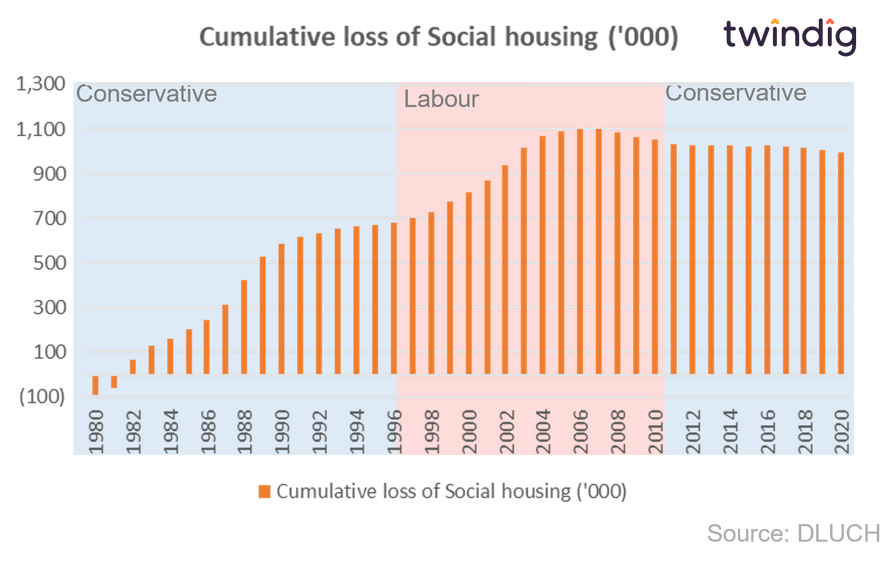

The chart below shows the cumulative loss of social housing calculated as social housing sales less social housing supply - if the balance is greater than zero more homes were sold than replaced.

No. Many of the homes purchased by tenants through the Right to Buy scheme are now owned by private landlords. In 2017 Inside Housing magazine estimated that 40% of Right to Buy homes were now owned by private landlords who were charging more than twice the rent charged by the local authorities for similar properties. Meanwhile, house prices over the last 42 years have increased by more than ten times to £289,099 in May 2022 according to the Halifax House Price Index.

The irony is that a large number of Right to Buy homes have ended up in the private rented sector where the rents charged to their current tenants are much higher than rents charged by local authorities and housing associations

Will the new version of the scheme be better?

Possibly. Housing Secretary Michael Gove promised that the Government would commit to replacing social homes sold off like for like:

“At the same time, we will continue to deliver much-needed new, good quality social homes by replacing each and every property sold.”

Michael Gove Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

But we question how that is possible, if homes are sold at a discount, where will the money required to replace them come from? This will only be possible in our view if the level of Government investment in housing increases significantly from its current levels

Will housing supply keep up with Right to Buy demand?

Many tenants will likely wish to purchase their home, especially if generous discounts are given and mortgages are widely available. However, we question whether housing supply will be able to keep up with the demand. The UK is already struggling to meet the Government’s housebuilding targets and so we are unsure as to where this additional supply will come from.

We may need to see a dedicated push for (and investment in) affordable housing of the scale we have not seen since the post-World War II building boom. Infrastructure investment and times of economic hardship are regular bedfellows, but we did not see in the Government press releases or hear in the media soundbites talk of significant additional funding for affordable housing.

Where will the new Right to Buy home be built?

Affordable housing needs to be built where there is affordable housing need. Transferring existing affordable homes into the private sector implies that replacement homes will need to be built elsewhere. One, therefore, hopes that the supply will be located in places of need, but that is perhaps easier said than done, especially in already built-up urban areas where much of the existing affordable housing supply can be found.

How will housing associations fund the additional housing supply?

Unless the Government provides (or underwrites) the cost of the replacement homes it is difficult to see how the new homes will be paid for. Many housing associations are already seeing their budgets stretched with remedial building safety works following the Grenfell Tower fire, and Right to Buy adds piles more problems onto their plates:

If you sell a home at a discount how do you bridge the gap between sale proceeds and build costs?

If the new assets you build run the come with the right to be purchased at a discount within three years how do you attract investors and funding when your potential cashflows have just been turned upside down.

We are huge supporters of homeownership, but there must be a better way

We think that a better way is through fractional homeownership.