Why rising mortgage rates might not hurt you

There is a lot of speculation that the Bank of England may increase the Bank Rate this week and further speculation that after a period of record lows, mortgage rates are about to rise. Rising mortgage rates are viewed as a bad thing, but in this article, we look at why the bark of rising mortgage rates may be worse than their bite and for many a rise in mortgage rates might not hurt at all.

What next for mortgage rates?

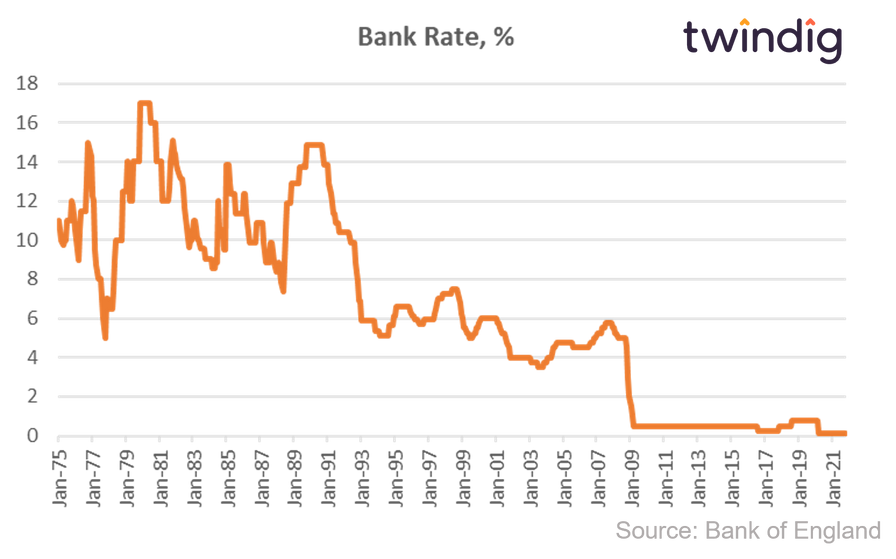

Bank Rate is the most important interest rate in the UK because the level of Bank Rate influences all other interest rates. The current Bank Rate is 0.1%, the lowest level since records began in 1694. From here, it seems Bank Rate is more likely (although not certain) to go up than down.

To put Bank Rate in context, it is currently more than 60x below its long-run average. The average Bank Rate since 1975 is 6.35%.

What will a rise in Bank Rate mean for my mortgage?

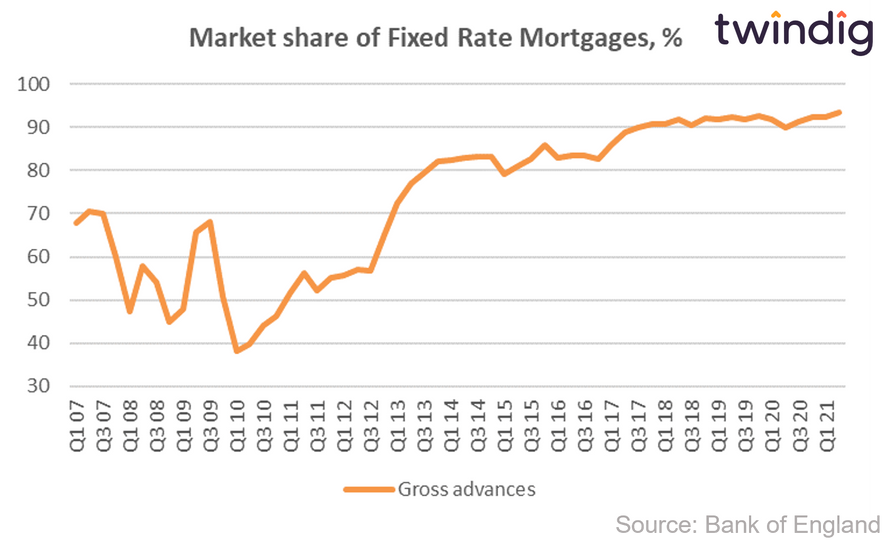

In the very short term not very much. Since 2017, on average, more than nine out of every ten (90%) of mortgages agreed have been fixed-rate mortgages. The mortgage rate on a fixed-rate mortgage cannot change during the fixed-rate period.

The most popular mortgage products are currently two year and five-year fixed-rate mortgages. In 2020 research from the Bank of England Blog Bank Overground showed that more than half of new mortgages in 2020 were fixed-rate mortgages with a fixed term of five years or more.

The key to whether or not a rise in mortgage rate will hurt is therefore not by how much the mortgage rates may increase by tomorrow, but

How long you have left of your fixed-rate period, and

How the mortgage rate you are offered compares to the mortgage rate you are currently paying.

How long have you left on your fixed mortgage term?

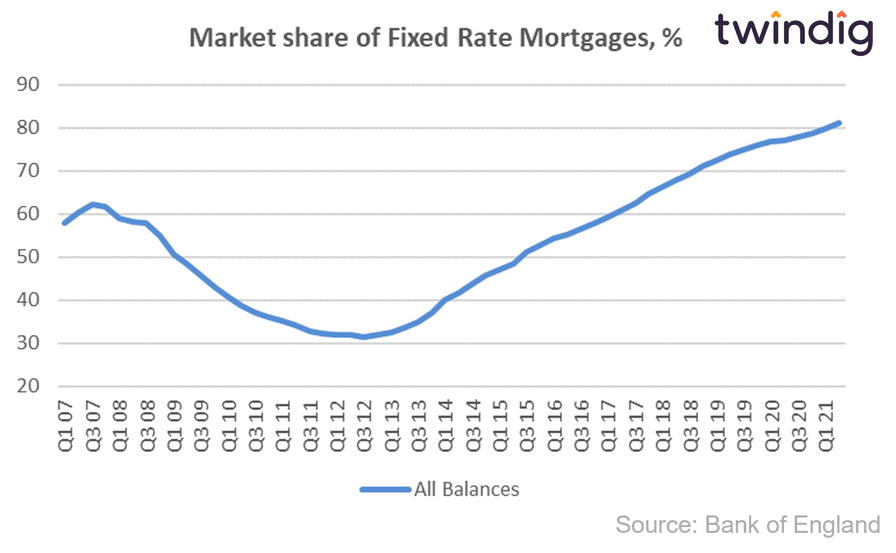

Across all the mortgages in the UK just over 80% are fixed-rate mortgages with most having a fixed term of between two and five years.

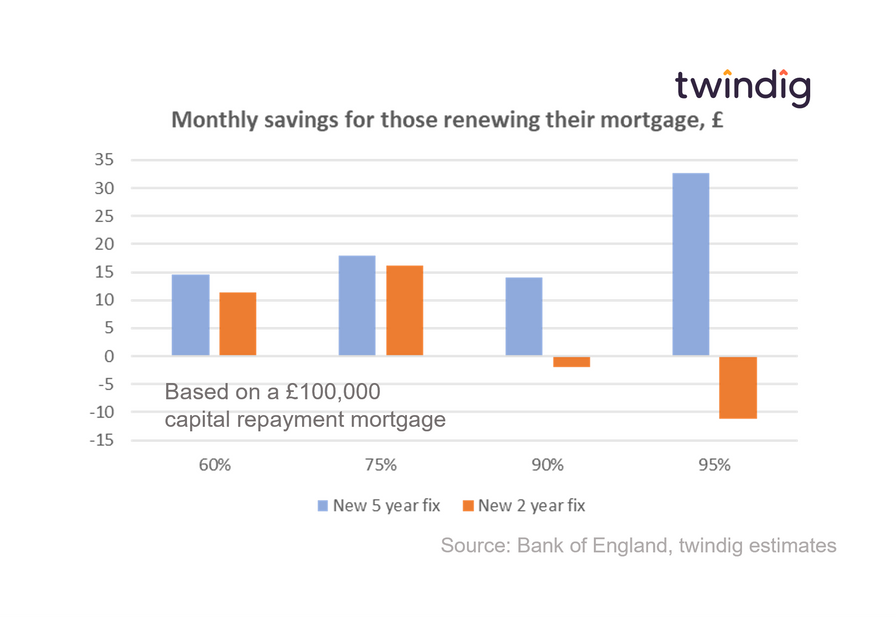

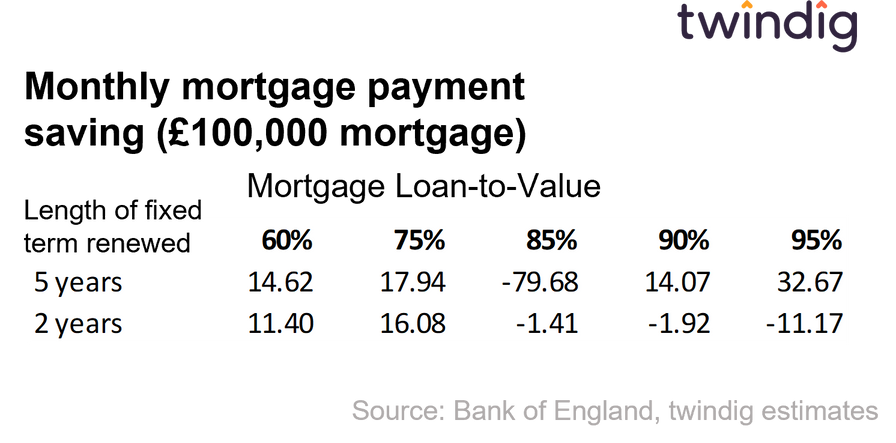

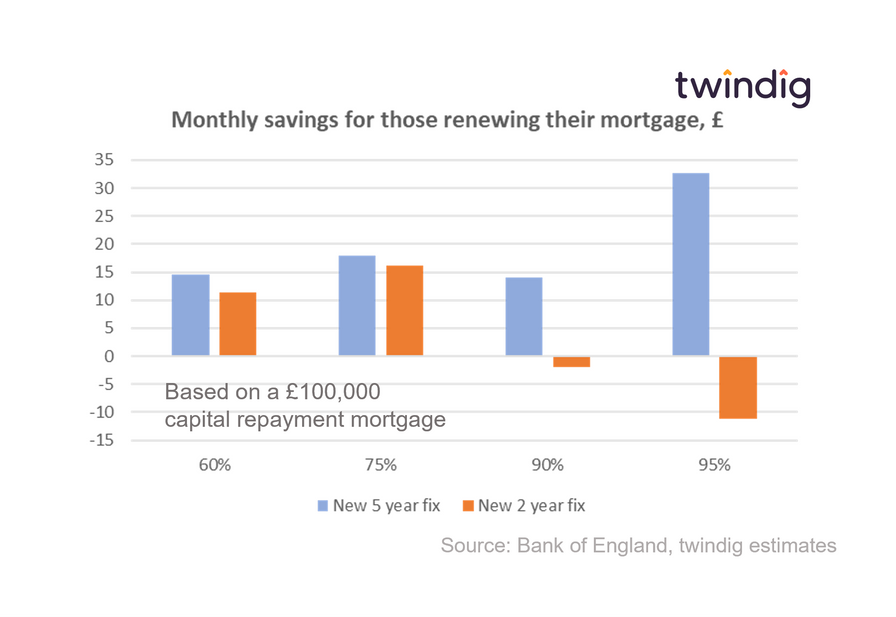

We look in the table below at how mortgage payments would change for a homeowner refixing a two or a five-year fixed-rate mortgage.

Even without taking into account the impact that mortgage payments and house price inflation will have on the loan to value ratio, it is clear from the chart that those renewing a five-year fixed-rate mortgage will be better off each month. Those on a two year fixed rate mortgage will be better off at the 60% and 75% LTV levels £2 per month worse off at a 90% LTV and £11 worse off per month at the 95% level.

If we factor house price inflation into the equation the savings are bigger. House prices have increased by more than 7.5% over the last two years, which means

a 95% LTV mortgage 2 years ago will be below 90% LTV today

a 90% LTV mortgage 2 years ago will be below 85% LTV today

a 75% LTV mortgage 2 years ago will be below 70% LTV today

a 60% LTV mortgage 2 years ago will be below 55% LTV today

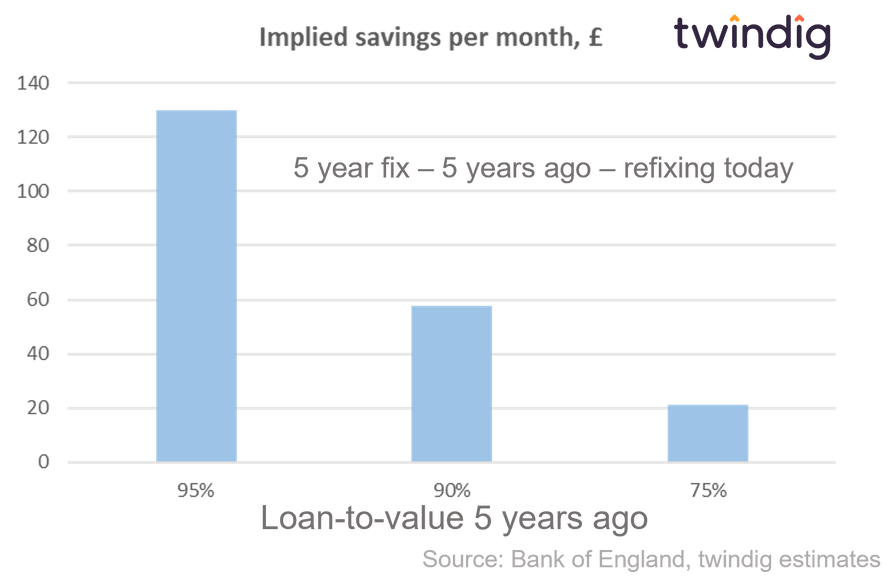

House prices have increased by more around 20% over the last five years, which means

a 95% LTV mortgage 5 years ago will be below 75% LTV today

a 90% LTV mortgage 5 years ago will be below 70% LTV today

a 75% LTV mortgage 5 years ago will be below 55% LTV today

a 60% LTV mortgage 5 years ago will be below 40% LTV today

What is Bank Rate?

Bank Rate is the most important interest rate in the UK. It is often referred to, incorrectly, in the news as the Bank of England Base Rate.

Why is Bank Rate so important?

The Bank of England Bank Rate influences all other interest rates, be that mortgage rates, savings rates or interest rates charged on loans and credit cards. When Bank Rate changes it normally follows that high street and commercial banks and lenders will change their interest rates on savings accounts and loans

Bank Rate in context

The current Bank Rate is 0.1%, the lowest level since records began in 1694.

The average level of Bank Rate since 1975 is 6.35%

Why are fixed-rate mortgages so popular?

Fixed-rate mortgages have become increasingly popular since affordability tests have been required as part of the residential mortgage application process.

The affordability test requires mortgage lenders to ensure that new mortgage borrowers could afford their mortgage if interest rates went up by 3% within the first five years of the loan.

Long-term fixed-rate mortgages (five years or more) are not covered by the mortgage affordability rules, meaning that lenders do not need to stress test these borrowers, and whilst this is perhaps a loop-hole for lenders to work outside of the affordability rules, the Bank of England’s analysis found that lenders typically stress test all borrowers, meaning long-term fixed-rate mortgages tend not to be treated differently.