Why house prices don’t need to fall to solve the affordability crisis

When we talk of a housing affordability crisis the consensus is that house prices need to fall to address the issue of affordability. We disagree. We believe the solution to the affordability crisis is to take a fresh look at the way we finance our homes.

Are house prices just too high?

There is a growing tension between the have and the have nots when it comes to residential property and the battle lines are drawn in several ways:

between older and younger households,

investors and renters,

homeowners and homebuyers, and

those with access to the bank of mum and dad and those without.

The argument in all cases is similar, those on the housing ladder have pulled the ladder up and out of reach of those either trying to get on the ladder or trying to climb further up the housing ladder. House prices are therefore too high, preventing those who want to get onto the housing ladder from gaining a foothold.

Market forces have forced up house prices

Blame is often put at the feet of free-market ideals which, some say, have turned our homes from a place to live into a financial asset, which in turn has pumped up house prices. Government policy should therefore seek to reduce house prices, to lower the ladder so that more can get onto it, rather than supporting a system that has increased the desirability of and demand for homeownership facilitating house price rises.

Let's build build build

The main policy response to the housing crisis is to build more homes, in the belief that prices are high because we have a shortage of homes, therefore increasing the supply of homes will alleviate some of the pressure on house prices.

House prices are unlikely to go down

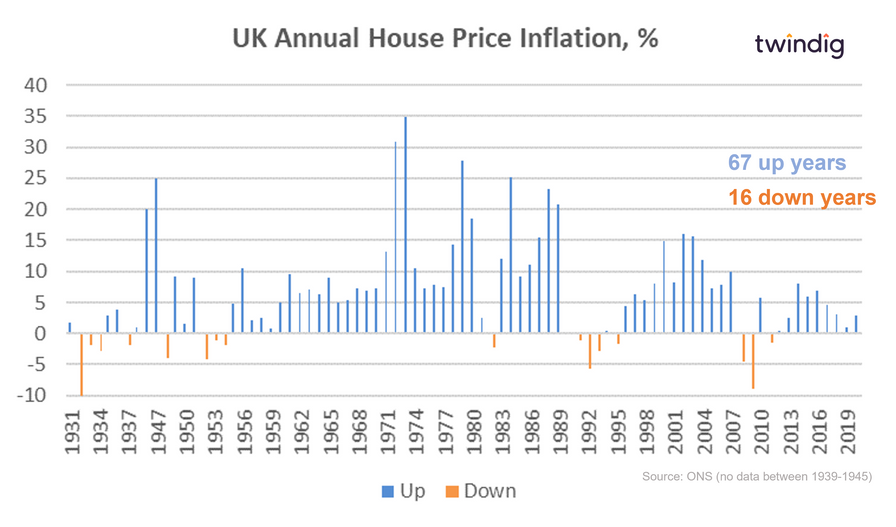

Whilst we should not use history to predict the future, history can teach us a lot about house prices. They rarely fall.

Since 1931 house prices have only fallen in 16 years.

But a house price crash is coming, right?

It is natural to think that after a period of significant, and unexpected house price growth house prices may fall. Few anticipated that house prices would rise so much during the (global) COVID-19 pandemic. As lockdowns led economies across the globe to enter severe recessions, house prices went up, and they went up a lot.

However, if we look at history house price crashes are very rare indeed. If ever house prices were to fall then the perfect storm was probably not the COVID-19 pandemic, but the Global Financial Crisis, which centred around excessive risk-taking by financial institutions in the residential mortgage markets.

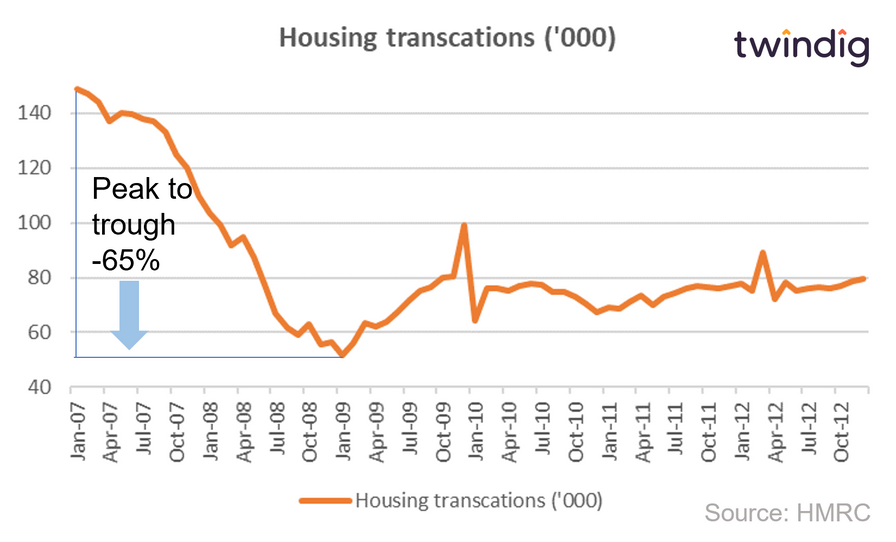

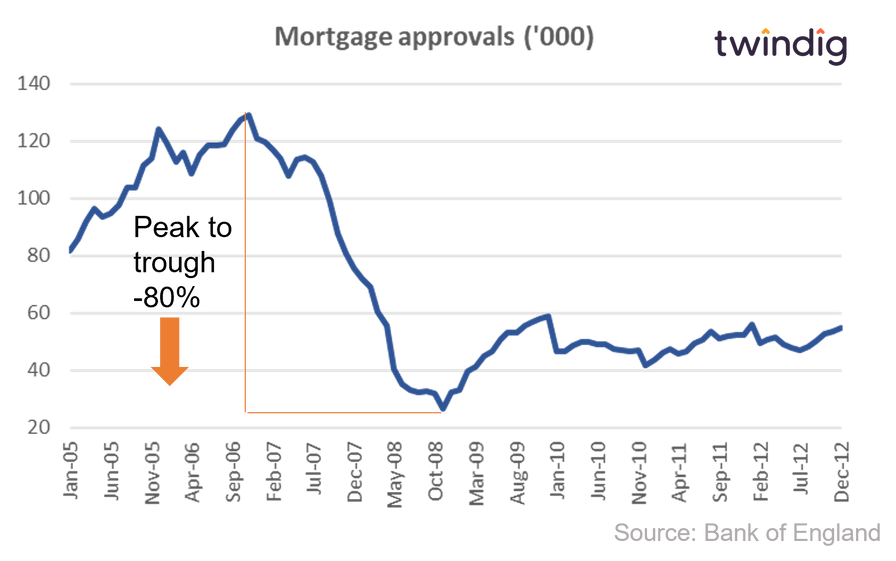

In the UK housing transactions and mortgage approvals plummeted:

Housing transactions fell by 65% from a peak of 149,510 in December 2006 to a low of 51,700 in January 2009.

Meanwhile, mortgage approvals fell even further, posting a peak to trough fall of 80% from a high of 129,000 in November 2006 to just 27,000 in November 2008.

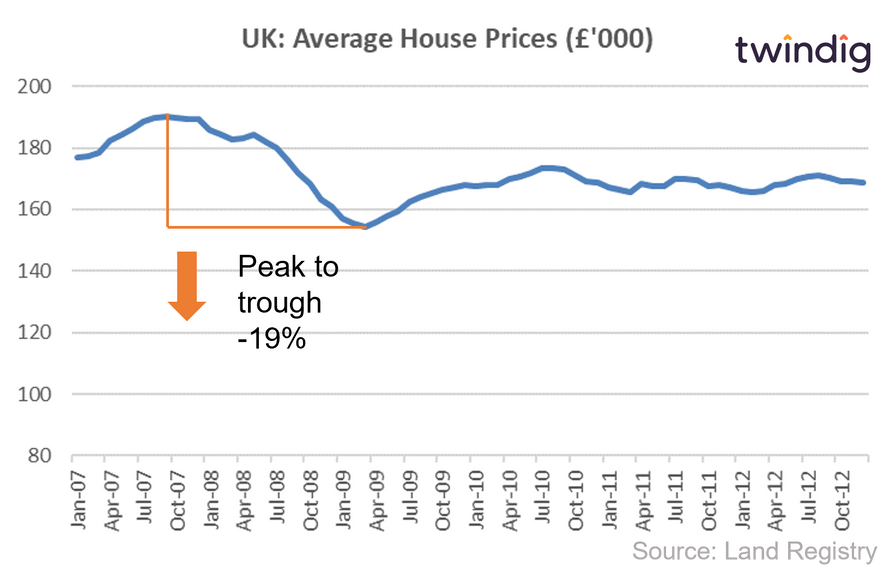

However, despite mortgage credit drying up and housing transactions falling like a stone, house prices didn’t really crash, they fell by less than 20% from a high of £190,000 in September 2007 to a low of £154,400 in March 2009 and then started going back up and today we have house prices which are more than 75% ahead of their prior peak.

We don’t need house prices to fall to solve the affordability crisis

At first glance, we don’t expect many to agree with our thesis, at first it seems counterintuitive, surely house prices must fall to solve the affordability crisis? Surely the problem is that low-interest rates and a ready supply of mortgages have allowed us to pump more and more money into the housing market which has led to significant house price rises?

However, maybe the two allegedly warring factions of those who want a home to be a home and those who see it as a financial asset can be on the same page and work together to provide opportunities to each other?

To take a fresh look at house prices, let’s get back to basics and take a look at why it is we want to own our homes.

Why do we want to own our homes?

The primary role of our homes is to provide shelter, which along with food and clothing make up our primary needs. The main benefit of owning our homes is that it provides security of tenure. If you own your home you cannot be forced to leave it.

Whereas when a home is rented the security of tenure for the occupants is not guaranteed.

Homes as a financial asset

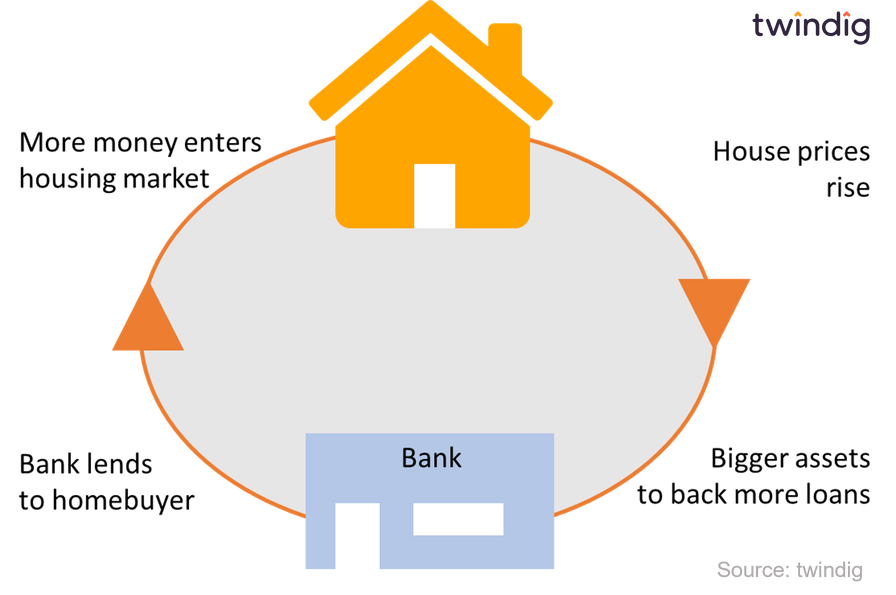

The desire to own our homes has led to a whole industry designed to help and enable households to buy their own homes. The mortgage industry is built on the premise that we want to own our own homes. However, by increasing the supply of money (mortgages) into the housing market we have inadvertently pushed up house prices, and the industry built around helping people own their own homes has, in part, made it more difficult to become a homeowner. The mortgage market has, say some, created the ‘housing finance cycle’

The housing finance cycle

If a shortage of supply isn’t increasing house prices what is?

One theory offered by economists such as Ryan Collins is the Housing Finance Cycle, which suggests that banks like lending on property because the loan is backed by a physical asset that can be possessed and sold if the loan is not repaid. The higher the value of the home, the higher the value of the loan that can be secured on it.

Classical economic theory suggests that as demand increases for a particular product the producers of that product will increase supply, if they can sell more and make more money why wouldn’t they? However, the housing supply response is slow. It is easier for a bank to create a new loan than it is for us to build a new house. If demand increases without a supply response, prices rise as buyers outbid each other to secure the scarce supply of products on offer.

In short, the housing finance cycle says that if the supply of loans is greater than the supply of homes house prices will rise and these price rises encourage the lender to make more loans because the higher house prices have provided a bigger asset on which to base the loan.

Homes as a financial asset

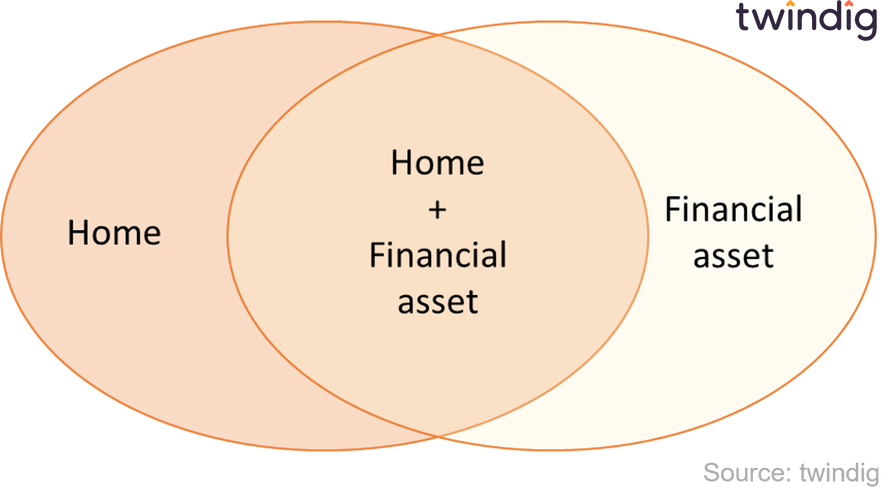

The impact of the housing finance cycle coupled with the long-term trend of rising house prices has created a dual purpose for homes, no longer are they just a source of shelter, but they have also become a store of value, a financial asset.

Compared to other financial assets, homes as a financial asset are easier to understand, we might not all have experience with bonds, shares and bitcoins, but we have all lived in a home and noticed that house prices tend to go up more than they go down.

But don't just 'blame' the banks

We must be mindful that the banks are not the only actors in the housing finance cycle, it is not just the mortgage market that has pumped money into the housing market:

Intergenerational wealth transfers

It would be unfair to point the finger solely at banks and the housing finance cycle for rising house prices. Successive governments from both the left and the right have encouraged homeownership, and the bank of mum and dad has, is, and will continue to pump a lot of additional money into the housing market.

Government policy

Successive UK Governments have actively supported homeownership through policy, ranging from taxation policy (gains on a homeowner’s primary residence are capital gains tax free) to policies such as Right to Buy, Help to Buy and those supporting shared ownership.

Can we put the financial genie back into the bottle?

We don’t think so.

Much of our current financial system has been built around the provision of mortgages. We doubt any Government will outlaw the bank of mum and dad.

The desire to own a home remains very high in the UK any policies designed to dampen that desire will be unpopular.

But we can change what the genie does and what the bottle looks like

We don’t think homeownership needs to be structured or considered as a binary outcome based on house prices

We believe that it is possible to create an environment where shelter is secure, and if shelter is secure then you no longer need to own a property to have a home. We also believe the same environment can also provide access to the housing market to all, this would mean that, if they wanted to, anyone could choose to gain financial exposure to the housing market, not just those towards the higher ends of the income and wealth scales.

Stop the housing cycle I want to get off..

In our view, there is a way to counter the unwelcome aspects of the housing finance cycle

Just as every coin has two sides, we believe that property can be both a home and a financial asset. Homeowner occupiers benefit from both sides of the coin, whereas renters and landlords will be found on different sides of the same housing coin.

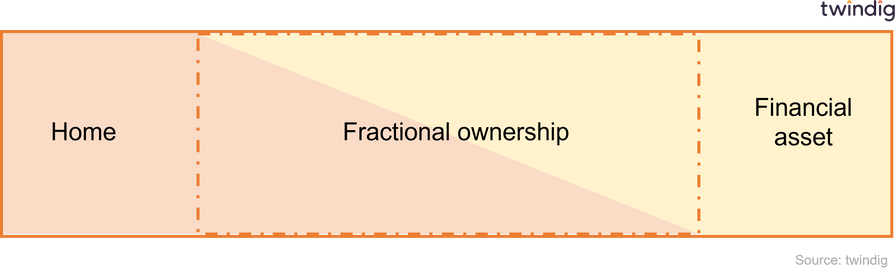

However, we see a world where rather than owner-occupation being an all or nothing affair, there is room for a sliding scale from part to full ownership.

We call it fractional ownership where instead of a landlord being pitched against the tenant, those looking for a home and those looking for a financial asset work together to help each other achieve their property-related goals.

Turning a financial asset back into a home

We think differently to most, whilst we agree that first and foremost a home should be a home rather than a financial asset, we believe that giving everybody access to the financial assets we call home is the best way to turn those financial assets back into homes.

We do not think that the housing finance cycle genie can be put back into the bottle. We, therefore, need to find a way for everyone who wants access to housing assets to be able to get access using the resources they have rather than those they don’t (a mortgage and/or a big deposit).

We can do this through fractional ownership. Fractional ownership is very widespread outside of the housing market, it's a system that works, but one that has not yet successfully been applied to the owner-occupier housing market.

Every stock market in every country in the world is built on the premise of fractional ownership. I may not be able to buy ‘google’, but I can buy a share in google. We aim to create a stock market for houses. This would take down the affordability barriers to housing ownership. We believe that it would democratise housing.

Rather than being either a renter or a homeowner, or being on or off the housing ladder, fractional ownership turns a binary situation into one with almost limitless opportunities for every stage between renting and full ownership.

Landlords working with homebuyers not against them

Being a landlord seems to get harder each day, tax breaks are being taken away and more and more regulations are coming into force. In our view, the increasing levels of rules and regulations are only seeking one thing to enable the renter to enjoy the provision of a safe and secure home. To re-stack the deck in the renter's favour.

We believe that all most landlords want from their rental properties is a steady income stream, tenants who look after their property and the prospect in the future of a capital gain.

The renter landlord issue is a classic case of the principal-agent problem – will the renter look after the asset that doesn’t belong to them, will the landlord provide a safe and secure environment for a home they don’t live in.

Through fractional ownership, both can own the home and both have a vested interest in looking after the home, this reduces the need for rules and regulations to make sure both parties are on the same page, because they will be on the same page.

Residential portfolio diversification

Homes are expensive assets and buying a home puts a lot of financial eggs into one basket, fractional ownership allows for that risk to be diversified across many baskets.

This is another way we see landlords and homebuyers working together, rather than buying one home, a landlord may choose to purchase 20% of five homes. These 20% stakes could act as the deposit used by the homebuyer. The landlord rather than being an adversary and competing against a homebuyer becomes a surrogate bank of mum and dad and helps the homebuyer purchase their home.

Deposit builders helping homebuyers

In our view, many would like to be able to save for their home by investing in the housing market itself, rather than putting money in a savings account or another form of financial asset that is unrelated to the performance of the housing market.

Fractional homeownership allows an aspiring first-time buyer the opportunity to buy part of a house as a financial asset to help them build their deposit to buy a physical home to live in.

This 'deposit' actually helps other first time buyers by acting as a quasi bank of mum and dad.

The deposit moves in line with the underlying housing market, and when the aspiring homebuyer has a large enough deposit in fractional shares, they simply sell them and use the proceeds of their financial asset to help them buy the physical asset they will call home.

The size of the fractional homeownership market

We believe that the potential size of the fractional ownership market is huge. The UK Government's Help to Buy scheme funds around one in three new home purchases and is worth about £4bn per year, however, new home sales only account for around 15% of housing transactions. This implies that a 'whole of market' help to buy scheme could be worth around £25bn pa.

Currently, around £50bn of money put into ISAs (around 70% of the total) each year is put into cash ISAs. If there was a true residential property ISA we would expect the demand to be high and would expect that households would consider spreading their cash ISAs between cash and residential property ISAs if the option was available.

If you would like to know more about fractional homeownership, you can read our 'Case for fractional homeownership' here